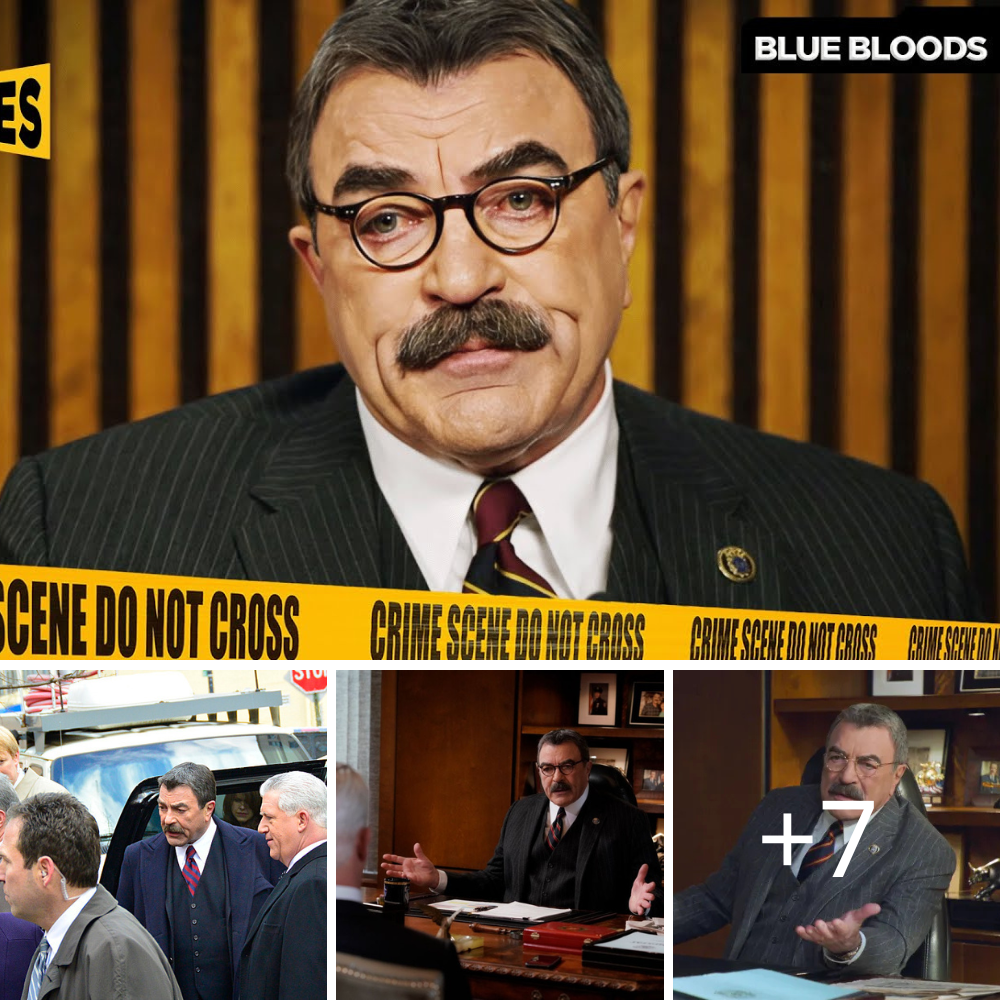

Frank Grilled By The Press About Race And Justice | Blue Bloods (Tom Selleck, Gregory Jbara)

Spoiler for the movie “The Commissioner’s Burden”

In The Commissioner’s Burden, the story unfolds around a painful reckoning within the New York City Police Department — one that forces its highest-ranking officer to confront the haunting consequences of a long-buried injustice. The film opens on a tense press conference, where Commissioner Frank Reagan faces a barrage of questions about six young men who have just been exonerated after spending nine years in prison for a brutal crime they did not commit.

The scene is quiet at first — cameras flash, reporters lean forward — and then the question lands: “Commissioner, do you feel personally responsible?” The tension in the room thickens as Reagan’s face hardens, the weight of the years pressing down. The case, a notorious gang rape that occurred the very night he was sworn into office, has resurfaced after the real perpetrator confessed from his own prison cell. Evidence once deemed “solid” has crumbled under the truth, exposing the system’s failure — a failure that happened under his watch.

Reagan responds carefully, his tone steady but haunted. He admits that the crime — and the miscarriage of justice that followed — took place while he was in charge. He reminds the press that at the time, every piece of evidence pointed toward those six young men: eyewitness testimony, forensic traces, and public outrage that demanded swift justice. But now, in hindsight, those so-called “facts” have been destroyed by the reality of a false conviction. The world knows the truth, and the city is demanding accountability.

When asked if he has personally reached out to the exonerated men, Reagan pauses. The silence stretches — heavy, uncomfortable. Finally, he confesses that he hasn’t. He hasn’t called them, hasn’t written, hasn’t faced them. Not because he doesn’t care, but because he doesn’t know what to say. “I can’t imagine what I could say that would mean anything,” he admits quietly. “And I still don’t.” With that, he ends the conference and walks away, leaving behind a room full of stunned reporters — and an audience full of conflicting emotions.

From there, the movie dives deeper into the emotional and ethical fallout of the revelation. Through flashbacks, we see the original case unfold: a city in panic, detectives under pressure, and a newly sworn-in commissioner trying to prove his leadership. The young men, all from marginalized neighborhoods, become the perfect scapegoats for a terrified city and a police department desperate to appear decisive. Prosecutors build a case on coerced confessions and circumstantial evidence, while the media paints the boys as monsters. When the verdict comes, Reagan stands before the cameras declaring justice served — an image that now haunts him.

Nine years later, DNA evidence and a prison confession blow the case apart. The true rapist, an already convicted murderer, admits to acting alone. The six innocent men are freed — broken, older, their youth gone. The city erupts with outrage and sympathy in equal measure. Some demand resignations. Others call for reform. But Reagan faces a deeper, quieter battle within himself: the unbearable weight of guilt.

The movie’s middle act follows Reagan as he grapples with his conscience. He reviews old case files, revisits the neighborhood where the arrests were made, and faces the detectives who built the case. Some still defend their work, insisting they acted on what they knew. Others confess to doubts they buried long ago. The truth is murky, filled with human error, fear, and institutional blindness.

Meanwhile, the six men — now grown and scarred by years of imprisonment — struggle to rebuild their lives. One becomes a community activist; another can’t escape his trauma and turns to alcohol. Their reunion scene is heartbreaking — a mix of bitterness and solidarity. When they receive a financial settlement from the city, the question arises: can money ever compensate for lost time? “How do you put a price on nine years of your life?” one of them asks, echoing the reporter’s question from the film’s opening.

In the third act, Reagan makes a choice. He breaks his silence and visits the men in person. The scene is raw and understated — no grand speeches, no easy forgiveness. Reagan admits that he doesn’t expect redemption, only the chance to look them in the eye. “I was the man in charge when the system failed you,” he says quietly. “That’s on me.” Some of the men listen in silence; one turns away in anger. Another simply says, “You came. That’s something.”

The encounter doesn’t resolve the pain, but it begins a fragile process of truth and reconciliation. Reagan later testifies before a reform commission, acknowledging the deep flaws in the justice system — the bias, the pressure, the human weakness that led to tragedy. He advocates for change in interrogation protocols, evidence handling, and public accountability. The film doesn’t frame him as a hero, but as a man finally confronting his own failures with honesty.

The final moments of The Commissioner’s Burden are quiet and contemplative. Reagan stands alone in his office, looking out over the city skyline as the evening sun fades. A recording of the press conference plays faintly on a nearby monitor — his own words echoing: “I can’t imagine what I could say that would mean anything.” He turns it off, takes a deep breath, and begins to write a letter. The contents aren’t revealed, but the act itself suggests a man trying, at last, to bridge the gap between regret and responsibility.

As the credits roll, archival footage of real-life wrongful conviction cases plays, grounding the film’s message in truth. The audience is left to sit with the same impossible question the movie began with: what is the value of nine stolen years — and can justice ever truly make it right?

“The Commissioner’s Burden” ends not with triumph, but with quiet accountability — a haunting reminder that the cost of justice delayed is humanity lost.