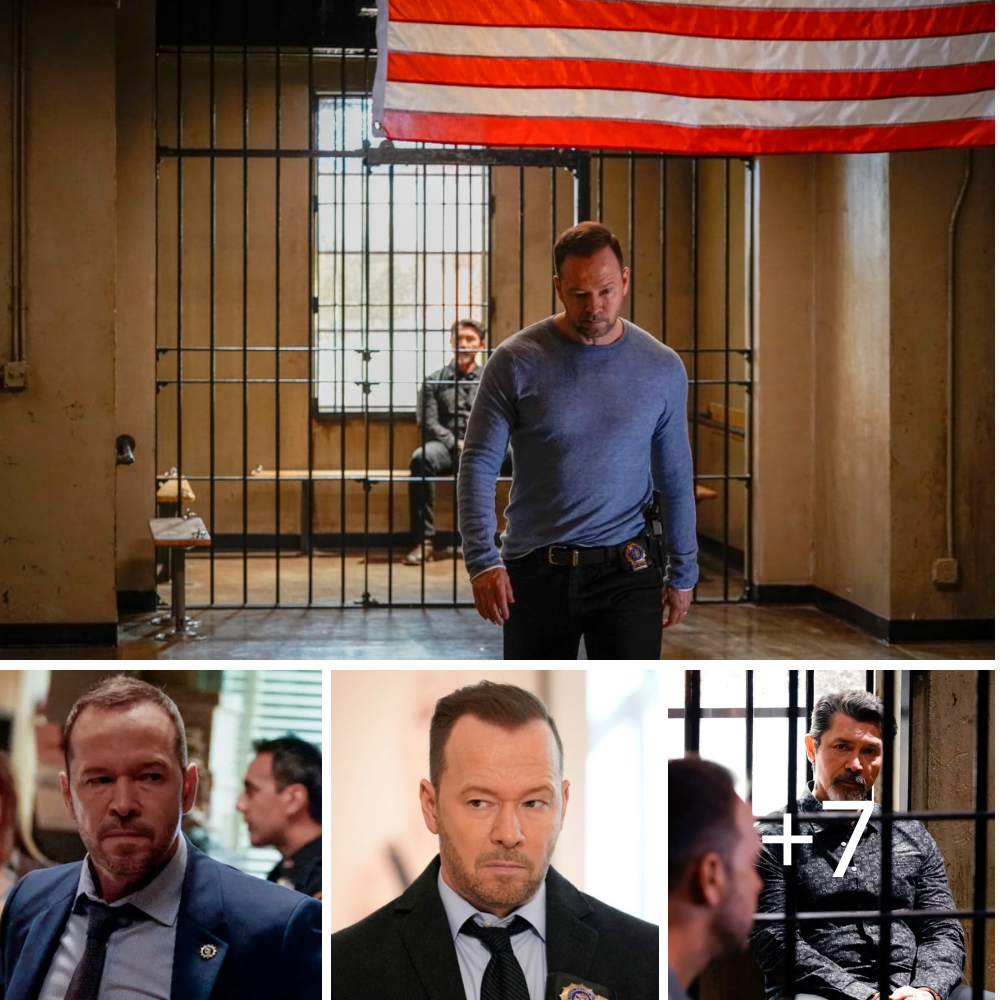

Danny Arrests Man Who Burned Down His House | Blue Bloods (Donnie Wahlberg, Lou Diamond Phillips)

Spoiler for the movie “Black Escalade” — Extended scene summary

They kick the door in like a moment from a nightmare — not the polite knock of officers with a warrant, but a hard shove and the flash of hands and guns. “Mr. Delgado, you can’t come in here without a warrant!” comes the shouted legalese, but the house is already ransacked by fear. Someone answers with a cool, raw edge: “The door was open. Somebody could be in danger. Come on, take a look.” It’s the kind of pretext that sounds lawful until the lights go out and the reality of a raid sets in.

For a breathless second, the apartment is an electric wire: flashlight beams, the whisper of boot heels, the clink of cuffs. A voice—thin with rage and panic—cuts through. “Don’t move. I’ll blow your brains all over that wall. Get your hands up now!” The threat is immediate, animal. An occupant is forced to the floor, eyes wide, while another voice, steadier but not gentle, barks orders. “Now come on, get him up.” The room is full of smoke and accusation.

“Partner, you okay?” a man asks, and the answer is brittle: “I am now.” The exchange has the coldness of people trained to survive violence. Then the scene pivots into law and badge: “You can’t arrest me — I haven’t broken any laws.” The man clutching his flannel is outraged and rightfully terrified. But the officer’s response is clinical, procedural and a little deranged: “Yes you did. You sold to the police officer. You didn’t even identify yourselves as cops.” It’s a phrase meant to strip dignity; it’s also a leverage point. The officer announces his name — “Detective Daniel Reagan. You ring a bell?” — a performance of authority that lands like a slap.

The accused is furious in a different register. “You have no right to keep me here,” he spits. “You came into my house without a warrant.” That grievance hangs in the air like an accusation that could undo everything: the façade of legal cover, the moral high ground of the police. Yet the reply is a steely, almost bored insistence: “Yeah I do. We assaulted a police officer. Now sit down and shut up.” The scene collapses into the murky space where law meets vigilant theatrics: they will do “what you cops do,” the occupant says — lie to get what you want.

Names are weapons here. The detective throws one out like a gauntlet: “You’re known as the Panther.” It’s not an accusation of fashion; it’s a label for a reputation, a cabal of crimes, a shadow identity. The man answers with angry denial: “I’ve never heard that name before.” Then the interrogation narrows — it becomes a clock. “How about Manuel Sanchez?” the detective presses. The room tilts under the weight of specificity. “Where were you yesterday between 12:00 and 5:00?” they ask, like mechanics testing an engine. The accused replies defiantly, almost petulantly: “I was home reading the Penal Code. I know when my rights are being violated.” He’s trying to turn law into shield.

But the officers don’t back down. Their memory is forensic: “You torched the cop’s house last year.” The charge lands heavy in the room; it smells of smoke and revenge. The accused protests with equal vehemence: “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” One officer flips open a pad with a grim frown. “Fine then,” he says, pulling a pen. “You can write down that you know nothing.” The bureaucratic flourish is a kind of mercy and a trap — record the denial, build the case.

Anger escalates into confession by accident. Someone in the room—another man with a chip on his shoulder—lets a voice crack across the scene. “Your house went up like a stack of kindling,” he says, and the words are not just description but a wound. “My only regret is that your family wasn’t in it at the time.” The sentence stabs. The accusation becomes a mirror: an admission of motive and of cold intent. It’s not a lawyer’s evidence, but a human confession. The room erupts.

“Hey! Cut it out!” someone cries. “He just admitted the burn of my house!” The admission ricochets. The accused’s face contorts at the injustice and cruelty; the officers exchange looks that are half-triumph, half-disgust. Someone else—Danny—reminds them all of the rules like an anxious parent: “We have to do everything by the book on this one.” It’s an odd, fragile attempt at procedural purity in a moment stamped with vigilante heat.

What unspools in the next few minutes is a careful dismantling of any simple narrative. The men who claim to be cops are not blameless instruments of justice; they are a hand that sometimes uses the law like a club. Their invocation of the Penal Code, their insistence on giving the accused the chance to “write down” his denial — these are legal theater. But the theater matters: it creates paper, it produces a trail that can be used later in court or as leverage in the quieter backrooms of power.

Meanwhile, the personal stakes spike. The thrown accusation that someone “torched the cop’s house” lifts the film out of procedural detail and into territory where vendetta and system overlap. A burned house is not just property damage; it’s a message. The regret expressed—“my only regret that your family wasn’t in it”—is the baring of a thirst for retribution. It signals that whatever codes these men live by, they are not above cruelty. They will answer fire with fire.

The scene is also a portrait of the film’s larger themes: law’s slipperiness, the ease with which rage masquerades as righteous anger, and the towns of people who are both victims and perpetrators. The detective’s name—Daniel Reagan—circles in the air like a promise of justice. But the film has been careful to show Reagan’s world is not black-and-white. He can cite statutes and carry a badge and still be the kind of man who moves with the law’s margins. He can call someone “the Panther” and demand accountability, but his tactics suggest that justice in this city is administered through intimidation as often as through indictment.

By the time the officers finish their paperwork and the apartment settles into a brittle quiet, the audience is left with an ugly truth: this is not a simple bust. It’s a message sent to a wider family, an escalation that will demand answers neither the law nor the vigilantes can fully control. The accused, breathing hard, knows his rights and yet feels them shredded. The officers know the rules and yet bend them. And somewhere beyond this apartment—on the street, in a burned-out house, in a courthouse—the ripple effects begin.

The last image of the scene is deliberately small and devastating: a pen scratching a name down on a form, a cigarette stub smoldering in an ashtray, a child’s toy half-covered in dust on a living-room floor. These ordinary objects are the collateral of a law that conflates justice with power. The camera lingers on them just long enough to remind you that every accusation, every confession, every raid has a human ledger—names, faces, and the possibility that, when the smoke clears, the people left standing might be only the ones who learned how to survive the flames.