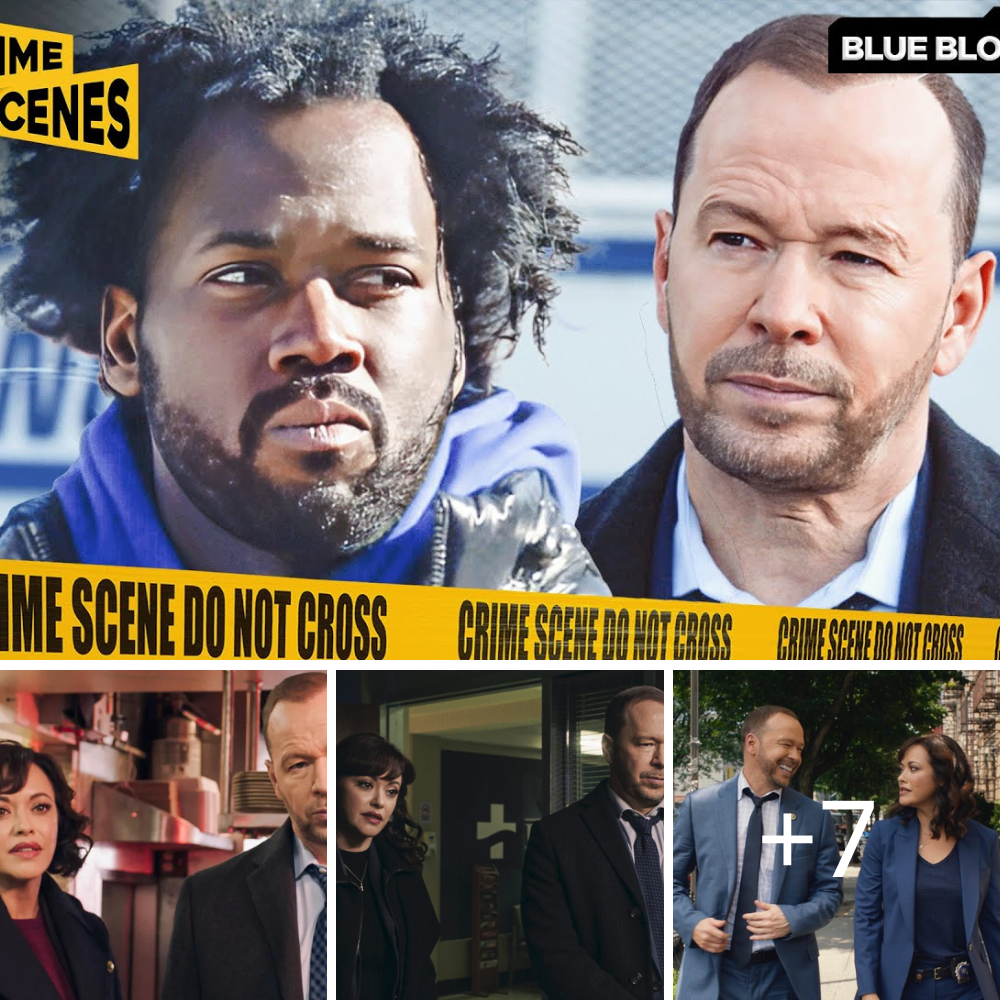

Detective Admits He Arrested Man Because Of His Race | Blue Bloods (Donnie Wahlberg, Marisa Ramirez)

Movie Spoiler for “The Theater District”

The film The Theater District begins like a typical police procedural — fast, direct, and full of tension — but soon unravels into something far deeper: a study of guilt, prejudice, and redemption set against the pulse of New York City.

Detectives arrive at a small, cluttered apartment. The man they’ve come for, Spencer Holland, stands frozen in surprise, holding a half-empty bottle. “Okay, first things first — put that down, step back over here,” one detective says, his tone firm but calm. The atmosphere is taut, thick with unease. The officers tell him they’re here to talk about an assault in the Theater District that happened a week earlier. Holland looks confused, defensive. He’s young — early twenties — and the camera lingers on his trembling hands. “See your hands?” the detective asks. “Any tattoos?”

They spot a small ink mark on his wrist — a faded fraternity symbol. “Looks like a frat tattoo to me,” the detective notes dryly. The music swells. Holland sighs, defeated. “Yeah,” he admits softly. “I feel bad about that dude.”

Then, without resistance, he begins to confess. The scene unfolds with a strange, almost weary honesty. He explains that the night of the assault, everything in his life had fallen apart — he’d failed a midterm, got ghosted by a girl on Bumble, and drank himself past reason. “The guy was some hick who got in my face,” he says bitterly. “I blew up. It was all me.” He laughs nervously, half ashamed, half numb. The detectives push him gently but firmly: “You hammered a complete stranger and stole his money.” Spencer shrugs. “Yeah. I needed cash to keep drinking.”

For a moment, it feels open-and-shut. The officers exchange looks. “That was easy. Case closed,” one mutters. Spencer asks, almost casually, “So I’m going to jail now, huh?” The lead detective nods. “Sure looks that way.” Spencer sighs, “Can I at least put on real shoes first?” “Go ahead,” the detective replies. It’s a small act of mercy, or maybe just routine.

But as he moves to retrieve them, something shifts. Another man enters the frame — a second suspect, quiet, serious, and visibly uncomfortable. His name is DeShawn Lewis, and he’s the reason the detectives are back on edge. Spencer’s story had matched details from the assault, but new evidence — a witness statement, a traffic cam still — suggests they might have grabbed the wrong man entirely.

In the next scene, DeShawn sits in the interrogation room, calm but cold. “Told you I didn’t do it,” he says. “Yeah, you did,” replies the detective, checking his notes. “But you did have a warrant.” “I didn’t do it,” DeShawn insists. The detective sighs. “I know.”

What follows is the emotional centerpiece of the film — a raw, deeply human conversation about justice, race, and responsibility. When DeShawn accuses him of racial bias — “Sorry, I didn’t hear it. It’s ’cause I’m Black, huh?” — the detective answers carefully, “No. It’s ’cause I’m a cop.” Then, after a pause, adds, “Both things can be true.”

That moment defines The Theater District. It’s not about the crime anymore — it’s about what happens when people confront their own biases in real time. The detective admits what few ever do: “I learned very early on that bad guys come in all shapes, sizes, and colors — Black and white. Good guys too. But I also learned that nobody can do this job without letting their personal feelings get involved. Sometimes we all make mistakes. Me included. And we can all do better.”

It’s not a speech meant to absolve him — it’s a confession of his own. The camera stays locked on DeShawn’s face as he listens, expression unreadable. “So what?” he finally asks. “Is this supposed to make everything all better?”

The detective shakes his head. “No. Not sure I can make it better.” He hesitates. “Maybe if you believe I’m telling you the truth… maybe that could keep things from getting worse.”

That single exchange — quiet, unglamorous, heartbreakingly real — becomes the moral spine of the movie.

The film then cuts to flashbacks that fill in the missing context. We see Spencer stumbling through the neon blur of Times Square, drunk and angry, lashing out at a man he misjudges as mocking him. The victim collapses; Spencer panics and runs. But unseen by him, another figure — DeShawn — was only a few feet away, walking home from a late shift, and was captured on a blurry camera near the scene. When the police pull the footage, they see only shadows — a Black man near a white victim — and the case snowballs from there.

By the time Spencer’s confession surfaces, DeShawn has already spent days in holding, his reputation in ruins. The system’s machinery has already stamped him guilty.

When the truth finally comes out — Spencer’s fingerprints on the victim’s wallet, the confession recorded, the timeline verified — the department scrambles to repair the damage. But the apology rings hollow. The film doesn’t offer catharsis; it offers realism. DeShawn walks free, but freedom doesn’t erase humiliation. Spencer is led away in cuffs, his drunken regret now a lifelong stain.

In the final act, the detective visits DeShawn at a community center where he’s helping with youth outreach. The meeting is awkward, understated. The detective hands him a copy of the report clearing his name, but DeShawn doesn’t take it. “You keep it,” he says. “You need it more than I do.”

The last scene mirrors the opening — same neighborhood, same city hum, but a different tone. The detective stands alone outside, watching kids play in the street. The sound of laughter mixes with distant sirens. His voice-over delivers the film’s closing words:

“The badge says protect and serve. But it never says from what — or from who. Sometimes it’s from ourselves.”

The camera pulls back, the lights of the Theater District flickering in the distance — a haunting metaphor for perception and illusion. The city looks beautiful and unforgiving, just like the truth.

In summary: The Theater District is a gripping police drama that transforms a routine assault investigation into a powerful exploration of prejudice, guilt, and accountability. Through the intertwined fates of Spencer Holland, DeShawn Lewis, and a conflicted detective, the film lays bare how justice can fail — and how redemption begins only when people stop defending their mistakes and start owning them.

The story doesn’t end neatly. Nobody walks away unscarred. But in the silence between two men — one falsely accused, one forced to face his own bias — the film finds its quiet, devastating truth: that acknowledging the problem isn’t enough, but it’s the only place real change can begin.