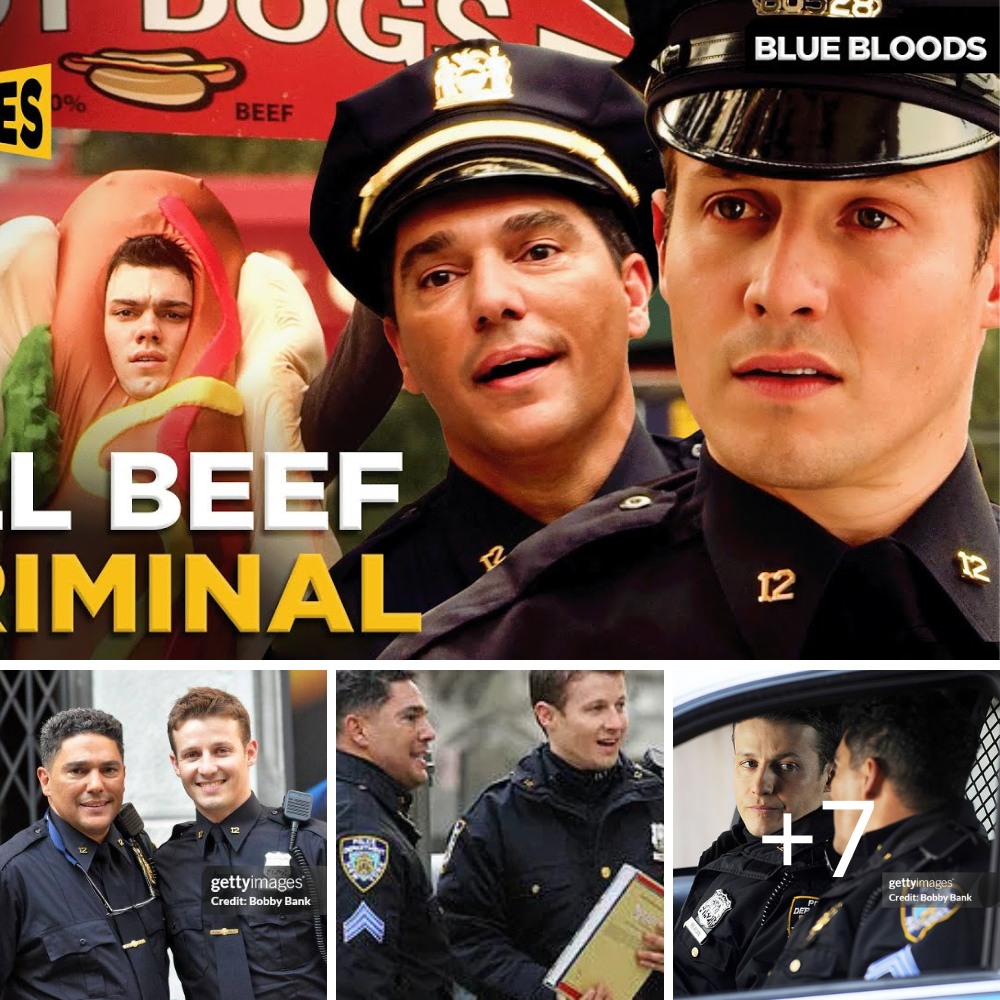

Arresting A Drug Dealer Dressed Like A Hot Dog | Blue Bloods (Nick Turturro, Will Estes)

Spoiler for the Movie: “Second Alert”

The film’s tense set-piece in the middle of the day turns a jokey costume gag into a moral and procedural crisis that exposes everything wrong with a system tuned to paranoia. What begins as casual banter among security officers quickly hardens into a full-blown arrest, and the scene becomes a microcosm of the movie’s central themes: fear, overreaction, and the way institutions can turn ordinary people into suspects.

They’re working off a recent alert — not the run-of-the-mill suspicious package calls that came after 9/11, the kind that usually amount to nothing. Instead, this one has the kind of credibility that makes everyone sit up. The protocol is clear: if there’s another alarm within the hour, you treat it as serious. The officers joke, try to keep things light, but you can feel the tension underneath. That nervousness is what the story latches onto: small signals amplify quickly in an environment wired for threat.

Into that charged atmosphere wanders a man in a hot-dog costume — a publicity gimmick, a street vendor, a bit of local color. One of the guards notices him and, with the loose, macho humor people use to mask unease, calls attention to the costume. “Hot dog, 12 o’clock,” someone jokes. Lunch is over; the moment is meant to be silly. But the team’s threshold for suspicion has been lowered. The film treats that lowering deliberately: a costume that should be comic becomes, through the characters’ eyes, potentially dangerous. Costumes hide things; the narrative insists, repeatedly, that “they hide all kinds of contraband up there.” It’s whispered as if saying it aloud will justify what comes next.

That whisper is the film’s acoustic provocation. The lead officer, already keyed by the earlier alert, tells the younger cop: do your job. Don’t stand around debating policy or worrying about the optics. Question him. Frisk him. The movie shows how quickly the dynamic shifts from casual to coercive — how the collective mood decides guilt before any evidence is produced. One officer points out that people wear humiliating outfits only if they’re getting something in return; the assumption slides from “why” to “what.” Unemployment is high, and desperation, the script suggests, can push people into odd jobs. That economic backdrop softens none of the officers’ suspicions; if anything, it hardens them, because it supplies a motive for illicit behavior.

The vendor is hauled off before he can fully register what’s happening. There’s a scuffle, shouted commands, hands grabbing. He protests, insists he has nothing illegal, asks to be let go. The camera sticks to his hands, the zipper lines of the costume, and the comic absurdity of a man in a mascot outfit being manhandled under the glare of security lights. The contrast is cinematic: playful costume versus the serious choreography of arrest. When the costume is opened, the payoff is immediate and ugly — a pocketful of contraband, prescription medication that shouldn’t be in a street vendor’s possession. The officers catalog it clinically: hydrocodone and other pills, plastic vials and foil packets. Someone jokes weakly about becoming a clown, about the indignity of having to wear that outfit — the film lets that gallows humor hang in the air so the audience can feel its wrongness.

From a plot standpoint, this arrest does a lot of work. It justifies the officers’ earlier anxiety: they did find illegal substances. It also escalates the situation: the team needs to process the suspect quickly and get back on the beat because a second alert (the “top priority” call) has just come through. The movie uses this ticking clock to ratchet up pressure. There’s no time for community policing, no time for nuanced interviews. The vendor is booked fast — cuffed, read his rights, and shoved into the car. “Get him in the car,” someone barks. The urgency is mechanical, almost bureaucratic. The officers are less interested in justice than in clearing the scene and responding to whatever the next alarm will be.

But the film doesn’t allow that neat, procedural conclusion to stand unexamined. Even as the scene resolves on screen — the arrest made, the pills documented, the costume stowed — the narrative invites doubt. How did those prescription drugs get in the vendor’s costume? Were they his? Did someone slip them in? Could economic hardship explain possession, or is there a larger distribution chain at work? The movie lingers on the small details to sow unease: a torn receipt, a delivery tag, a look exchanged between two background characters. Those micro-clues are the director’s way of telling us that the visible arrest is only part of the story.

Thematically, the sequence serves as a condemnation of quick-trigger suspicion. The hot-dog costume becomes a symbol of the way society’s protective systems — security alerts, police protocols, public fear — can turn everyday life into a staging ground for humiliation. The film is merciless in showing how dignity is stripped in public: a man who was trying to make a living becomes a poster child for a department’s anxieties. The officers, who could be seen as heroes for their vigilance, are also revealed as complicit in a system that privileges speed over fairness. Their banter — “go get him,” “do your job” — is not neutral. It’s performative, designed to absolve them of second thoughts.

There’s also a subtler critique of performativity in the uniforms themselves. The vendor’s costume, meant to amuse, is weaponized by the narrative of suspicion. The officers’ uniforms, meant to signify authority and protection, become instruments that enact that suspicion. The film stages this inversion deliberately: the very outfits that signal safety are the ones that facilitate injustice when wielded unreflectively.

What follows the arrest in the larger arc is where the movie really lands its themes. The discovery of the pills triggers an internal investigation, a neighborhood uproar, and the involvement of a social worker who suggests that the man might be a small-time peddler caught up in a bigger trade. The vendor’s friends and family are interviewed; they speak about dwindling opportunities and systemic neglect. The film doesn’t excuse illegal activity, but it pushes the viewer to consider context — poverty, mental health, the collapse of community supports. In that sense, the hot-dog arrest becomes a hinge: it marks a turning point where personal responsibility and institutional failure are put on the scales.

There’s also a procedural fallout. The second alert that forced the officers to move quickly turns out to be another false alarm — a misread parcel, a nervous passerby. That reveal is devastatingly anticlimactic. The movie uses it to ask: what is the true cost of acting on fear? The vendor’s life has already been disrupted. Even if the charges are later reduced or dropped, the humiliation and the paperwork remain. The film’s courtroom scenes later underline this: defense lawyers and prosecutors argue not just about the pills but about the reasonableness of the stop, the search, and the rush to judgment. The judge’s admonitions about probable cause and the need for corroborating evidence are dry but necessary, and they frame the moral inquiry the movie wants us to have.

By the end of the sequence — and indeed by the film’s end — the hot-dog costume arrest remains emblematic of the larger tragedy. It’s a simple scene, stretched out into a parable about how modern security culture commodifies fear and how that fear, once institutionalized, can devour the vulnerable. The movie doesn’t offer easy answers. It shows the arrest, the paperwork, the theory that maybe the suspect was just a pawn, and it leaves the audience to sit with the uncomfortable truths: systems designed to protect can also punish; jokes can become justifications; and in a world of constant alerts, the human costs can be swift and unforgiving.

In short, what should have been a comic interlude becomes the film’s indictment: in a climate of suspicion, nobody is really safe — not even the man dressed as a hot dog.